letter #7: Vivere Ancora

from Southern Italy

A few days ago, I stood in front of an abandoned stone farmhouse where my grandfather was born in early March 1923, just outside of Morcone in Southern Italy. The swooping branches of fig trees are slowly obscuring the house, and dusty, cracked windows give just enough visibility to see the bottles and torn envelopes and rusted farming tools left behind by whoever lived here last. The house sits relatively high on a hill, overlooking rolling farmland, a lake, and a sprawling grove of olive trees. My relatives, who I stayed with in the nearby village of Campolattaro, believe the house could be almost 200 years old, predating the risorgimento — the unification of the Italian nation-state in 1861. I circled the house a few times, crawling through thorny vines while looking for evidence of my grandfather’s existence — a delusion I found amusing since he hadn’t lived in the house since at least 1940.

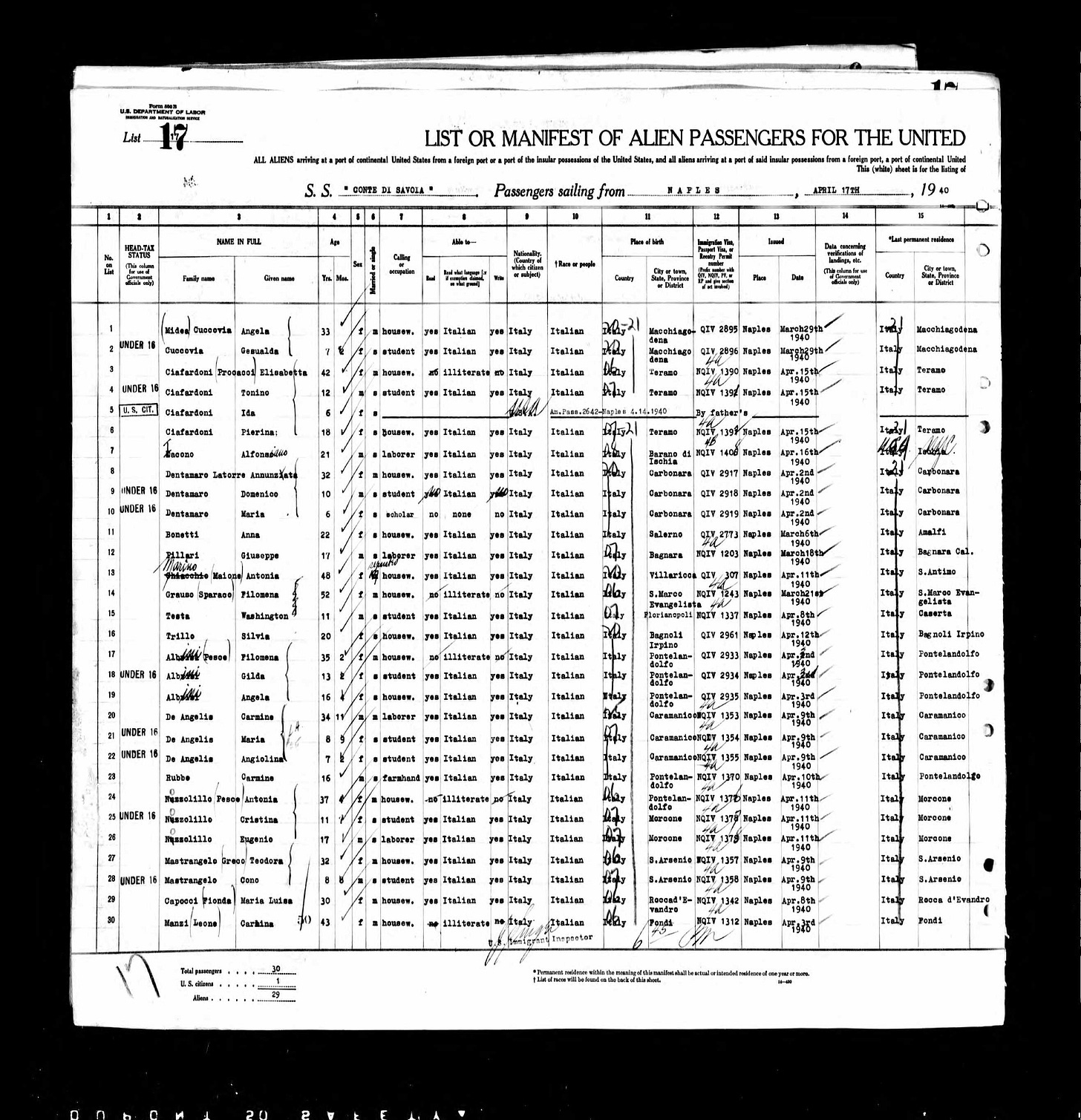

My grandfather — we, the grandkids, called him Papi — sailed from Napoli with his sister and mother on April 17, 1940, on one of the last American-bound journeys of the S.S. Conte di Savoia. It was then or likely never to join his father in New York for the promise of a better life, with the Second World War looming over their journey — Italy entered the war only a few months later in June.

I found a passenger manifest for the Conte di Savoia online, which lists “Eugenio Nozzolillo,” 17, his sister Cristina, 11, and his mother Antonia, 37. Eugenio, who would become Eugene, my namesake, was listed as a laborer, 5 foot 1, with fair complexion and chestnut hair and eyes. The manifest also asks and answers: was he an anarchist?1 No. Was he a polygamist? No. An advocate for the overthrow of the U.S. government? Also, no. Near the end, the document lists the first place they’d live: 33 Henry Street, Inwood, NY with my great-grandfather, Libero, also known as Benny.

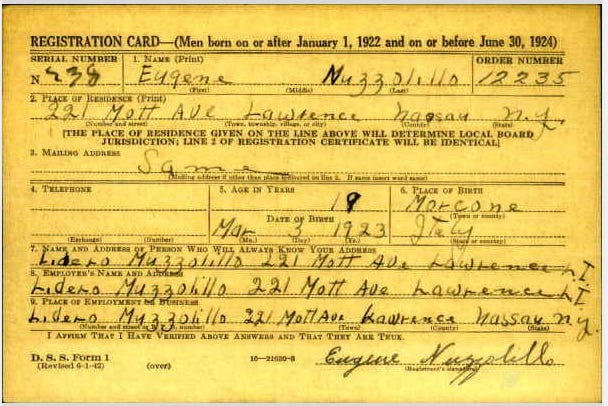

About two years later, a World War II draft card (never invoked, thankfully) lists new details about my 19-year-old grandfather. He now lived at 221 Mott Avenue in Lawrence, NY, had grown to 5’4’’ tall and 125 pounds; was of “ruddy” complexion and hazel eyes. In July 1945, he married my grandmother, Marie Russo, and their wedding photo is the first glimpse I have of him as a young man.

Within a few years, they’d relocate to an Italian enclave in Southington, Connecticut where my aunts, an uncle, and my Dad were born. A 1963 city directory lists his occupation as a plasterer. Eventually, he’d get a job repairing electric motors at GE, where he stayed until he retired.

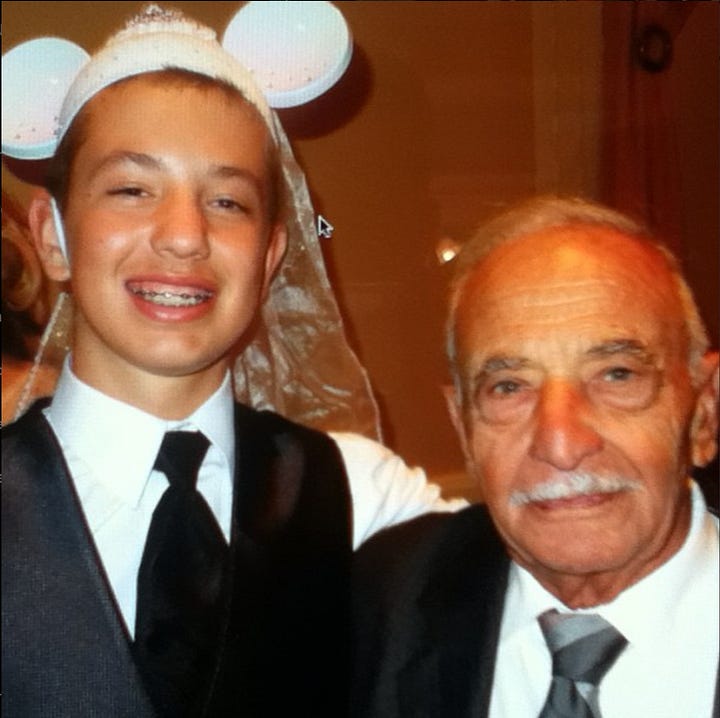

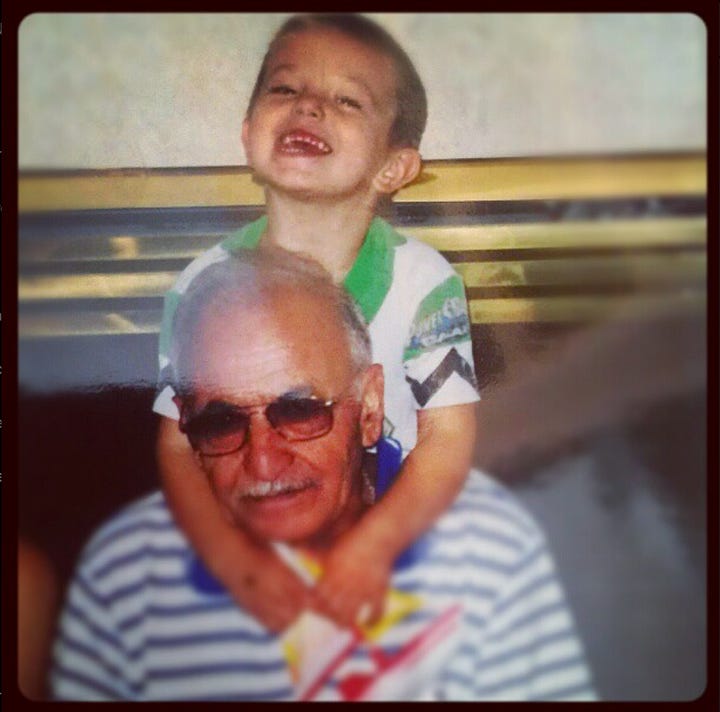

The rest of what I know about him comes from brief childhood memories and family stories. I remember the long hours he’d spend up and down the lines of his garden, how’d he make taralli and pasta by hand every morning, how Caillou and Steve Irwin were the only shows I could watch on his TV because he didn’t have cable. He was no-nonsense, indefatigable; fastidious in taking care of his family. I can still hear his thick Italian accent adding a musicality to the voicemails he’d leave on our landline for birthdays and holidays. Once, he told me he didn’t approve of the long shaggy hair I’d grown in elementary school to be more like Justin Bieber. Later, I’d come to appreciate his honesty.

One of my favorite stories: in the 1970s, my Dad spent a few years living and working on the farm with our relatives in Campolattaro, the same place I just left. When it started to seem like my Dad might not ever return, my grandfather, bewildered, flew to Italy to bring him back. It was inconceivable to him why my Dad, with a college degree, would choose to work in the same fields my grandfather, with only a 3rd grade education, had worked so hard to leave. My Dad, stubborn, defiant, waited a few more months before finally returning to Connecticut. I’m sympathetic to the strong will they both possessed — I certainly inherited their stubbornness.

Papi died beloved, on January 5, 2013, nearly 90 years old. I was 14. I still grieve the time I didn’t have with him, the chance to know him as an adult, the questions I wish I could ask, the unending gratitude for all his sacrifices which I was too young to appreciate or convey when he passed. I miss him.

Spending the last few weeks in the region where he grew up has renewed my sense of losing Papi, if only because his past is becoming more vivid to me. I crafted my time in Southern Italy with the intention of following in the footsteps of him and my Dad, albeit briefly. I spent two weeks living and working on a family farm in Sant’Agata dei Goti, about an hours’ drive away from Morcone. Starting at 7am, alongside the farm’s owners Pietro and Antonella, I dug holes, weeded, harvested Aglianico and Montepulciano grapes, planted fig trees, weeded, turned over soil, cut trees, and pulled more weeds. I ate my meals with them, stumbled through Italian limited to a handful of often-repeated vocabulary and the forever present-tense (I’m getting much better, though!), and spent the rest of my time reading and writing. After leaving their farm, I spent a weekend with my Campolattaro relatives — the first time I’d seen them in nearly 20 years — who told me stories about Eugenio and Giuseppe (my Dad) and never stopped feeding me. This time has been a gift.

While I’ve been in the relatively quiet countryside, Italian cities have been consumed by massive protests and labor strikes in solidarity with Palestinians. The protests are an attempt to pressure Italy’s right-wing government, led by the neofascist party Fratelli d’Italia, into taking a stronger stance against the ongoing genocide, especially in light of the Global Sumud Flotilla’s attempt to break the siege surrounding Gaza. Reports from this past weekend put the number of attendees at over 2 million. Dockworkers shut down the port in Livorno, students occupied universities, and schools and trains were closed because of striking workers. The photos and videos of what’s shaping up to be Italy’s largest protest movement in decades are incredible. The historical echo of these protests rings even louder in light of the fact that they take place almost exactly 82 years after a similar mass revolt against fascists and genocidaires in Napoli.

The wind stops and the storm calms,

the proud partisan returns home,

blowing in the wind his red flag,

victorious, at last free we are.- From the popular Italian anti-fascist folk song “Fischia il vento”

World War I produced an economic crisis in Italy, with rising prices and high unemployment driving dramatic growth in trade union, socialist, and anarchist formations. Industrial and farm workers called for democratic control of the economy, seizing abandoned farmland from landlords, occupying factories in cities like Torino and Milano, and joining over 3,000 strikes between 1919-1920. This period came to be known as the “Biennio Rosso,” or the Two Red Years.

The revolutionary potential of this moment in Italian history was eventually undermined by mass layoffs and wage cuts, a lack of support from the more reformist Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and General Confederation of Labor (CGL), and reactionary violence against striking workers by fascist paramilitaries called the Blackshirts, who were supported by major landowners and corporations. By October 1922, just a few months before my grandfather was born, the counterinsurgency succeeded in bringing the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini into power as prime minister.

Mussolini spent the next few years consolidating control and deploying violence against socialist and communist political opposition, notably taking responsibility for the assassination of socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti in 1924. Through a series of laws, the fascists formally outlawed the existence of other political parties and labor strikes, made Mussolini virtually unremovable from his position, and by 1928 abolished parliamentary elections. His government spent much of the next decade launching brutal invasions in Ethiopia, Albania, Greece, and Yugoslavia as an attempt to create a “new Roman Empire,” a prelude to Italy’s alliance with Nazi Germany and entry into World War II.

Mussolini’s Italy, generally unprepared for war, collapsed by 1943 due to internal revolts and the Allied invasion of Sicily. A mass strike of over 200,000 workers in Italy’s industrial north had destabilized the regime. Most Italians, suffering from intense supply rationing and famine, welcomed the invading British and American forces as liberators. By late July, Mussolini had been forced out of power and the remaining leaders of Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, formally ending its involvement in the war.

However, the liberation of Italy from fascists had only just begun. The Nazis moved to occupy the northern half of Italy, rescuing Mussolini and establishing a puppet state called the Italian Social Republic. The Nazis held control, though volatile, as far south as Napoli, where clashes between residents and soldiers intensified. In late September, about a week before the Allied powers would enter the city, the German commanders declared all men aged 18-33 would be deported to forced labor camps in Italy; to refuse or resist would mean execution. When the Nazis attempted to enforce their order, a spontaneous and decentralized eruption of rebellion took place. Neapolitans sabotaged German operations, stormed barracks and distributed weapons, and children as young as 11 fought the Nazis in chaotic urban combat. From September 27-30, the Italians succeeded in driving the Nazis out in what became known as the Four Days of Naples.

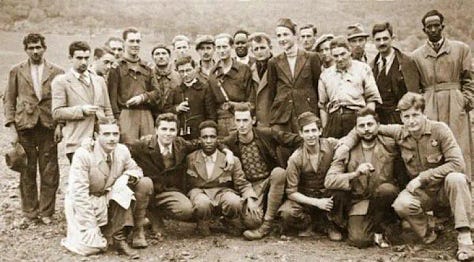

The Neapolitan victory marked the first major act of resistance by a growing movement of resistance fighters called I Partigiani — the Partisans.2 Across the country, an unwieldy coalition of communists (the largest group), socialists, liberals, Christian Democrats, and various antifascists organized as the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (CLN). While the Partisans largely held together in driving out the Nazi occupiers, political divisions were already apparent — the communist and anarchist factions largely saw the resistance as the seeds for a revolution in Italy post-war, whereas other groups held more moderate goals to simply restore pre-Mussolini parliamentary democracy.

Nonetheless, the Italian Resistance Movement sustained a grueling and bloody guerilla campaign, as much an effort to force out the Nazi occupiers as it was a civil war against the remaining Italian fascists. Fighting in the mountainous regions of the Alps and Apennines, as well as in the Po Valley, partisans carried out assassinations, sabotage, skirmishes, and coordinated with industrial workers in major cities like Bologna, Torino, and Milano. Women partisans played indispensable roles as fighters, message couriers, and safe house operators, and despite the sexism of male partisans, pursued the resistance as not only a question of national liberation, but also emancipation from patriarchy and misogyny. Partisans faced horrific reprisals from the Nazis and their Italian collaborators. German commanders vowed to kill 10 Italians for every German killed by partisans. Around 15,000 civilians, mostly women and children, were subject to these indiscriminate massacres and war crimes.

By the end of April 1945, the Partisans achieved total victory. Their forces freed the city of Bologna, and a popular insurrection among workers and everyday citizens, similar to the one in Naples, liberated other major Northern Italian cities. Mussolini, attempting to escape to Switzerland, was captured by communist Partisans and summarily executed. By the end of the conflict, over 50,000 partigiani had been killed. Tragically, the postwar period in Italy would betray the courageous sacrifices made by the Partisans who liberated Italy, especially communist industrial and farm workers.

By 1948, the Italian Communist Party had surged in popularity, numbering over 2 million members and occupying powerful positions in the new Italian Republic. Many of the new Communist Party members joined because of the potential for radically reshaping the Italian economy, as well as to deliver on consequences for former fascist leaders.

However, the political fissures barely contained by the CLN during the war soon burst open. More moderate factions wanted a return to normalcy and a “progressive democracy.” Corporations like Fiat, who had previously allied with Mussolini, saw an opportunity to quell worker action and made common cause with liberal Italians and foreign powers like Great Britain and the U.S., who already started to play Cold War politics in seeking to counter communist political strength where it existed. Communist leaders like Palmiro Togliatti, the Minister of Justice in the new Italian government, then compromised with other political parties to implement the “Togliatti Amnesty” in 1946. In sum, the Amnesty generally pardoned the former fascists, allowing many to avoid incarceration, while the law paradoxically treated the partisans more harshly, opening them up to greater prosecution and social harassment.

Parliamentary elections in 1948 brought a center-right government into lasting power — the Christian Democratic party would lead Italy until 1981 — dealing a severe blow to Italian communists and their dream of a transformed society. General strike action and industrial revolt would continue through 1948, especially after an assassination attempt on Togliatti. However, the pacifist and reformist approach advocated by high-ranking communist party leaders like him had already dramatically weakened their movement. The failure to fully prosecute former fascists and their collaborators contributed to a wider “amnesia” about Italy’s crimes under Mussolini, allowing the ongoing contestation over the legacy of the partisan resistance in Italian historical memory as well as the emergence of a new fascist political party in 1946. This party, the Italian Social Movement, is the forerunner to the modern-day political party Fratelli d’Italia, whose leader Giorgia Meloni serves as the Italian Prime Minster today.

The history of the Italian Resistance Movement illustrates the immense sacrifice and effort of ordinary people who risked everything to defeat fascism. Moreover, it shows what happens when politicians work against the aspirations and contributions of working-class people and fail to hold to account those who commit crimes against humanity. The testimony of Elsa Pelizzari, a former partisan, stated in an interview before Meloni’s party came to power in Italy in 2023, remains prescient: “[Young people]: you have to carry forward the antifascist spirit that has animated us all our lives.”

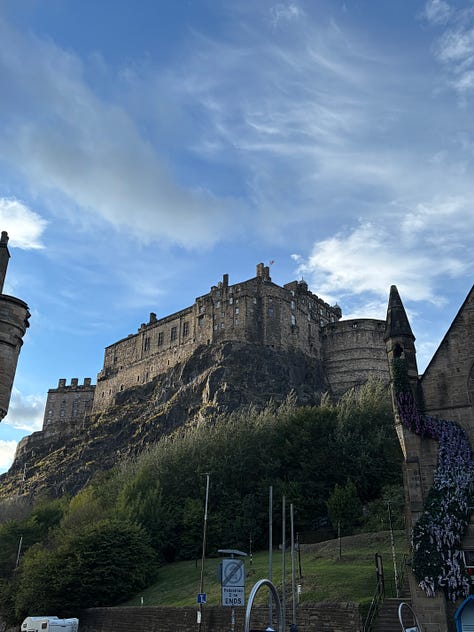

The start of my (mostly) solo global backpacking included some time in London and Edinburgh. I particularly adored the moody, melancholy beauty of Edinburgh’s architecture, and made some wonderful friends at my hostel. I’m writing this letter to you now from the Pugliese village of Polignano a Mare, which sits on the Adriatic Coast.

What I’m reading: Just finished Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward and Catcher in the Rye and I really loved my friend Trey’s recent essay on the connections we can draw between James Baldwin and Beyoncé.

What I’m listening to: your new playlist — try “Vivere Ancora” by Gino Paoli; “Fischia Il Vento” performed by the Modena City Ramblers; and of course, Bella Ciao. Fun fact: most historical evidence points to Bella Ciao only becoming popular postwar, rather than serving as a partisan anthem during the conflict. It still goes hard! But the original version of Bella Ciao, likely originating in the late 19th century, actually came from a group of women called “Mondine,” who sung about their exhausting labor in Northern Italian rice fields, and their struggles against cruel bosses.

What I’m thinking about: grad school applications. don’t ask! i’m warning you!

Un abbracio e alla prossima,

Gino

Anarchist political activity flourished in Italy, especially in the marble-producing town of Carrara. It’s a pretty interesting history, though I’m guessing 1940s-era U.S. customs officials weren’t asking new immigrants about anarchism for intellectual reasons.

Most of my understanding of the Partisan movement comes from an excellent four-part podcast series produced by “Working Class History.” Their series heavily features translated testimonials from actual Partisans who fought in the resistance.

Not sure if you’re taking book recs, but while in Italy (or even if you’re not) Elena Ferrante is a must!!

A beautiful read! Thank you 😘